![]() Compared to its neighbouring countries in Europe, Jews in Hungary WW2 were relatively safe up until March of 1944. Jews fleeing genocide in Germany, Austria, Poland and Slovakia sought refuge within Hungary’s borders.

Compared to its neighbouring countries in Europe, Jews in Hungary WW2 were relatively safe up until March of 1944. Jews fleeing genocide in Germany, Austria, Poland and Slovakia sought refuge within Hungary’s borders.

Horthy had managed to maintain Hungary’s autonomy to some degree, and had resisted German demands to deport Hungarian Jews to concentration camps.

But after the Germans invaded Hungary in March of 1944, the situation deteriorated drastically.

Peace for Jews in Hungary WW2?

It was March 19th, 1944, a quiet, sunny Sunday morning, when our good neighbours came running to call us into their apartment and listen to the radio.

It was playing military music, which was usually the forbearer of bad news.

Horthy, the leader of Hungary, made the announcement.

The Hungarian government had ceased all military activity against the Soviet Union. Hungary was asking for a separate peace from the Allies.

Peace! We celebrated, thinking that this was the end of our suffering and oppression.

But by that afternoon, the music had changed. To German military marches.

Our neighbours’ radios were playing the music loud enough that we could hear it clearly through our open window. We looked at each other, pale and trembling.

The almost panic-filled voice of the announcer came on the air saying that further announcements could be expected any minute.

We knew then and there that there would be no peace. It turned out that the attempt had failed. Germany had invaded Hungary.

German Occupation

Germany had known about the ceasefire, and even before Horthy’s radio announcement, the German army had crossed the Austrian border into Hungary. By the time the radio announcement came on,

German soldiers were already taking up positions in every Hungarian city and town, occupying the whole country.

It was all over for us. We would not survive this war after all.

David and I stepped aside, as far away from Mother as possible. We didn’t want to make her any more anxious, yet we had to discuss this turn of events.

David made it clear that he wasn’t going to be dragged into the ghetto and certain death. My own resolve began to take shape: I would not surrender.

As a Jew in Hungary WW2, I would find a way to survive, on my own, if necessary.

Alone

This must all sound like a lot for a twelve-year-old to handle. But I had no choice.

There was no one to discuss things with, no one to consult. Just days following the German take-over, David was called up for labour camp.

So I couldn’t talk to David or my father. And I didn’t have the heart to ask Mother questions; she had enough on her mind already.

Our gentile friends, whom we saw sporadically, couldn’t possibly understand the confusion and fear that I felt.

All the speculations and rumours were gloomy, predicting that the Polish experience would soon be repeated in Hungary. And by then, we all knew how the Jewish community had been murdered there.

Bombs Falling!

Soviet, British and American air forces began attacking Hungarian cities daily, primarily Budapest, in the spring of 1944.

A strict curfew was imposed and all light sources – from homes, businesses, cars, even bicycles – had to be blocked.

When air raid signals sounded, we took our blankets and emergency kits (with bandages and food) and headed down to the shelter.

Our concierge had cleaned out the basement storage area and converted it into an air raid shelter. He was the master there, assigning space to each family and generally maintaining peace and order.

Blankets were spread out and candles lit. We soon overcame our embarrassment over appearing in nightgowns and dressing gowns in public.

Some people would start conversations, cautiously avoiding talk about the air raids. Others brought down candles and books, and retreated behind their book covers.

As the the bomb raids became more frequent and more intense, the scenes in the shelters grew uglier.

There were territorial disputes. Someone’s legs were too long and stretched into the space of another family.

If a stranger happened to be around, he or she was eyed with suspicion and people grumbled about how valuable space was being used up. Gradually, the grumbling turned against Jewish residents.

They blamed us for the bombing attacks, us and our allied friends.

As the complaining turned into vicious verbal and sometimes physical attacks against Jews, it became more dangerous for us to go to the shelter than remain in our apartment.

So after a few weeks, we began ignoring the sirens. We still got up, dressed and prepared our emergency kits.

But we stayed put inside the apartment, remaining as quiet as possible, as it was an offence not to go to the shelter.

Later, Jews in Hungary WW2 weren’t allowed into the shelters at all.

Accused of co-operating with, or of at least being sympathetic towards the enemy, we were ordered to stay in our homes and were thus put at maximum risk.

Fireworks in Hungary WW2

I used to sneak out to our rooftop and crouch down beside the wall to watch the air raids.

While watching, I would make a silent prayer that the bombers manage to hit their targets and return in safety to their bases.

Some people went crazy with fear, hearing the whistle of the bombs. In the dark of night, each whistle sounded as if the bomb was headed straight towards my hiding place.

Smaller planes would appear in the sky, rapidly descending on the larger bombers. These were the Hungarian and German fighter planes.

The chasseurs (which both carried the German insignia of the Luftwaffe‘s double cross), trying to shoot down the heavy bombers, or at least force them to abort the bombing raids.

Individual “dogfights” would develop between the fierce attackers and the more defenceless bombers. I saw some spectacular ballet being performed in the air by these flyers.

One night, a refinery storage tank, a few hundred yards away, received a direct hit. The heat of the flames hit my face.

I lay flat on my stomach, afraid to inhale the hot air, afraid to move, for fear of being detected from the air or the ground.

The night was so bright, I worried that the pilots would see me lying on the rooftop, that they would know I was Jewish, and that they’d drop another bomb, aimed at me.

Another night, the target was the railway line, not far from us. They missed their target and hit an apartment building, practically next to ours.

Our building shook violently and the sound of shrieking and moaning filled the air.

Firefighters raced to the building, air wardens were yelling at the top of their voices. One could almost smell the acrid scent of charred bodies.

The next morning, whispered news confirmed that almost all the residents, trapped in the shelter underneath the rubble of the building, had perished. Damage to our own house was limited to broken windows and blown-in doors.

Another time, a large bomb landed just outside of our building. It dug a deep crater in the ground but didn’t explode.

If it had, it would have wiped out our building and all of us with it. The following morning, the army sappers arrived and cordoned off the area.

We were evacuated from our apartments and ordered to disappear until the bomb was diffused. All of us, some twelve families, became instant refugees.

The others went to the nearby church, while we were taken in by our good friends and neighbours.

The bomb was diffused a few days later, but it was left there for the remainder of the war, fascinating us children with its silent threat. The ground we used to play our war games on was now the playground for a real war.

Harsh New Measures for Jews in Hungary WW2

The man who arrived with the German occupational forces, Adolf Eichmann, didn’t waste any time introducing harsh new measures.

Anti-Jewish orders appeared daily, posted on walls all over the city:

- Jews were ordered to hand over all items of value: jewels, coins, foreign currency, etc.

- Jewish presence in any business or professional activity was forbidden.

- Jews were only allowed to be outside during certain hours of the day.

- We were banned from all public places, except stores. We couldn’t use streetcars or taxis; we weren’t allowed to attend any public performances, movies, theatres or concerts; and we were forbidden to eat in restaurants.

- By April 3rd, every Jew was required to wear a yellow star.

Jews had to leave their homes to go to the ghetto or into designated “yellow star buildings.”

We had to make immediate adjustments to our daily routine. Our lives were drastically altered.

The Yellow Stars for Jews in Hungary WW2

We had to immediately put stars on every article of clothing we might ever wear outside. Being outside without a yellow star on had become a punishable offence.

Mother was busy for days, sewing yellow stars onto our clothes. She made large, loose stitches so they’d be easy to rip off, if necessary.

Our survival depended on this ability to anticipate what was coming and prepare alternate plans.

Going outside wearing the star was a horrible experience, especially at first.

I tried to establish eye contact with people to convey a plea and also measure their reaction.

Reactions were varied: some people looked away. Some lowered their eyes as they passed me.

Some looked straight back with a mocking grin on their faces; others expressed their disapproval of the entire Jewish race.

Anti-semitic comments always had to do with being dirty, lice-ridden and sub-human, deserving of the worst fate.

The Arrow Cross party members (the Hungarian fascists) could now readily identify Jews and attack their targets more easily.

The mindless, vicious attacks that ensued were humiliating and threatening. In retrospect, these attacks were like warm-up exercises for both the victims and the victimizers.

I was never slapped or physically abused in the streetcar, the way I had witnessed some older Jews being attacked.

No one spat in my face or knocked my hat off. I was and am thankful for these small mercies.

Breaking the Rules

Since Jews in Hungary WW2 could only be out on the street at certain times, we couldn’t go to school any more. We couldn’t go to the stores to look for left-over food.

We couldn’t travel long distances for fear of not being back home on time. For me, this represented an irresistible challenge: to be outside during “illegal” hours without the mandatory star.

I regularly went out without a star on to roam around the street, pick up a newspaper or buy an ice cream cone. And I visited our store every day.

Although we weren’t allowed to go to restaurants or movie houses anymore, I didn’t want to give up my movies, so I continued going.

This scared my mother stiff. But because I didn’t look Jewish, I was never caught.

Occasionally, an acquaintance would notice me without the star on, point at his or her heart, and mouth “no star,” instead of reporting me to a policeman.

Although I broke the law daily, the fear of being attacked on the streetcar or in the streets was always with me.

The streetcar was regularly stopped by Arrow Cross bands who would come on the car and yell out:

“Any Jews here?! Does anybody see any Jews here?”

If they did, they would be dragged out and beaten up, then left on the streets of the ghetto, or the fascists would take them to a wall and shoot them.

Ugly scenes played out on the streets more and more often. Red-faced “patriots” insisting that a Jew be arrested for not wearing the star, while the police reluctantly performed their distasteful duty.

Sometimes, a police officer would just issue a warning and then tell the “criminal” to disappear quickly. In the early months of spring, policemen still behaved with a degree of decency.

Such simple acts were so outstanding, they begged the question.

Why didn’t more people behave with decency when this was quite possible?

Deportation for Jews in Hungary WW2

![]() Eichmann arrived immediately after the German occupation and set about his “task” of liquidating the Hungarian Jewry.

Eichmann arrived immediately after the German occupation and set about his “task” of liquidating the Hungarian Jewry.

The word “deportation” quickly became part of our vocabulary. Officially, it meant moving all Jews from the countryside to areas in the east.

There they would be resettled and allowed to live and work peacefully.

In reality, it meant:

- Being ordered without warning to pack a small bag and report to a specific point, like an abandoned factory or a stone quarry.

- Being marched through the streets of towns and villages, with gentiles lined up along both sides.

Some looking on sadly or crying, but most of them smiling with satisfaction and expressing their support for the heinous treatment being meted out to Jews.

During these marches, many of the sick and elderly were shot or beaten to death on the road if they were unable to keep up.

- Travelling in packed cattle cars, locked up, with even the windows covered with barbed wire, to an unknown destination, an unknown fate.

At the train station, there was confusion, shouting and yelling as one group after another was pushed up into cattle cars.

- Finally, deportation usually meant being killed in the gas chambers of one of the concentration camps.

Within three months of German occupation, between April and June of 1944, 400 000 Hungarians were deported from the countryside to concentration camps and murdered.

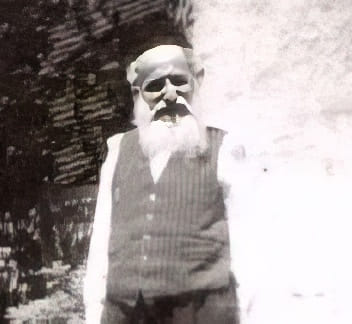

My uncles, aunts, nieces and nephews were among them. My grandfather, Abraham Salamon, died on the train on the way to the camp.

Only 150,000 Jews were left living in ghettos or yellow star buildings in Budapest.

Trains rolled through Budapest at night. A long row of cattle cars, doors padlocked, windows covered with barbed wire, an open car at the front and one at the back, packed with armed soldiers.

Occasionally, a night train would stop at some station and voices were heard from behind the wired up windows, begging for water or medical help.

This went on for four months. That’s how long it took to kill Hungarian Jews in the death factories of Auschwitz.

Railway Transports for Jews in Hungary WW2

Railway stations were guarded by soldiers and declared out-of-bounds to the civilian population, so we were unable to help the victims with food or water supplies.

But the railway workers were there and heard the cries and pleadings. Some risked their own safety to smuggle cans of water into the cattle cars.

Or pick up little pieces of paper thrown out through the barbed wire-covered windows, with names and phone numbers of relatives to call.

The workers delivered these sad messages and proved to be decent human beings.

Our home was close to the railway line. I often felt tempted to watch these trains roll by. But that was one thing I never found the courage to do.

I was afraid to see those trains. Perhaps I feared seeing the face of one of my relatives peering out through the wired-up small windows.

Or hearing their cries for help, as the trains rolled by. We had countless family members – grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins and others – living outside Budapest.

Mother and I knew that we would probably never see any of them again.

We in Budapest were protected from deportation for the time being. We were kept alive so we could be used as pawns for future negotiation.

As long as the liquidation process was going on in the countryside, Eichmann was satisfied and was willing to bide his time.

![]() We knew which towns were being emptied and when. Frequently, pieces of paper were thrown out of the train windows.

We knew which towns were being emptied and when. Frequently, pieces of paper were thrown out of the train windows.

Each naming the locations the “passengers” were from and sending messages to their surviving relatives in Budapest.

We also knew that the whole horrendously large and complex exercise was carried out entirely by the Hungarians. Usually the gendarmes were responsible for the rounding up of Jews at the train stations.

Here, mostly Hungarian and a few German soldiers assisted in the loading onto the cars.

Supposedly, the liquidation of the Hungarian Jewry was carried out by fewer than 200 German soldiers.

Our Home Is Confiscated

![]() On April 4th, it was announced that all Jews in Hungary WW2 were to move into designated buildings marked with yellow stars.

On April 4th, it was announced that all Jews in Hungary WW2 were to move into designated buildings marked with yellow stars.

That meant the end of our freedom in the suburb where we lived. The nearest such building was attached to our synagogue, which had long since ceased functioning.

Mother managed to get a room for us in the house, including shared use of the kitchen.

A few days later, we left our apartment. Carrying only some hand luggage and bedding, and closed the door behind us. I was heart-broken.

Our furniture, clothing and everything else was left behind, including my beloved violin. It all happened so fast that I didn’t have time to say goodbye to our neighbours or our home.

Mother must have suffered terribly. She had to leave all her treasures, her kitchenware, her clothing and accumulated possessions from two decades of married life.

These belongings later disappeared from our apartment.

Yellow Star House

We moved into the small building with a large yellow star on the front door. We were one of four families crammed into that building which had originally housed just one.

Each family had one room, and the kitchen and bathroom were shared by all of us. The cantor and one of the other families each had a young daughter.

I became very close friends with these two girls, and we set up a play school together. The important thing was to stay busy and keep our spirits up.

Our fathers and older brothers were all away in forced labour camps, somewhere on the eastern front. We shared a common anxiety about their safety, and fear for our own future.

There were surprisingly few arguments and clashes considering that we were confined in such a small space, twenty-two hours a day.

After a short while, there was a serious water shortage and it became impossible to take showers. So the women set up a rotation system, whereby each family would take turns using the kitchen to wash up.

A small wash basin was filled with water and served as a mini-bathtub. Carefully leaning over it or straddling it, one could perform the needed washing.

It was embarrassing to strip naked, but each of us was honour-bound to avert our eyes from the “bathers.”

David’s Escape

A few months after David reported to labour camp in March of 1944, he escaped and headed home. Stationed in a town not far from Budapest, he had heard rumours that they would be shipped to the east.

He made up his mind to risk immediate death rather than chance a slow, prolonged one.

One day, while marching back to camp from work, he didn’t turn the corner like he was supposed to, but kept going straight. In the dark, no one saw him and he kept marching straight to Budapest.

Fortunately, he was wearing civilian clothes. Good-looking, with what the mad Nazis considered solid “Aryan” features, he returned home without being challenged.

He even managed to hitch a short ride. While crossing a bridge, he encountered a group of young Nazis guarding the road.

He approached them with a loud fascist greeting and asked for fire to light his cigarette. He was allowed to continue, uninterrupted.

When David entered our house, everyone accepted the risk of hiding him in our room. He could not, of course, ever leave the building.

So he spent his days reading and playing chess with one of the men in our house, Bela Salamon.

Bela Salamon

There was a single man living with us called Bela Salamon. He was a tall, strongly built young man, who was exempt from forced labour on account of his being a deaf-mute.

A very intelligent man, Salamon managed to communicate extensively with us. He taught me both lip-reading and sign language.

Bela was a sweet, soft giant- strong but patient and quiet. Also a chess genius.

We would spend hours every day playing one game after another. Needless to say, he beat me almost all the time.

Salamon did not survive the war. Later that summer, one of the raiding parties took him away to a labour camp, refusing to accept his handicap as reason for exemption.

Once there, not understanding the orders given to him and not understood by the soldiers and guards, he was beaten to death by an enraged, shovel-wielding Hungarian soldier.

We heard this tragic story shortly after his death and I grieved as if I had lost a member of my own family.

I have never known a gentler, better human being. My heart aches even today when I think of him.

David’s Close Call

By early June, mob rule began to take over in the city. The Jewish yellow star houses were frequently raided by young Arrow Cross members and policemen.

The alleged purpose of these raids was to verify that no one was hiding inside without proper papers, to confiscate illegal radios, etc.

The real purpose was to steal and rob whatever caught the eyes of the raiders. If any resistance to the robbery was attempted, the residents were beaten up or arrested. Or they were beaten up and then arrested.

These raids were totally random and the police were often reluctant partners who were forced to participate.

Shortly after David’s return home, our house was raided. One day, we heard someone banging violently on the outside door.

Looking out through the peephole, we saw a handful of young fascists and two policemen carrying heavy weapons over their shoulders.

As we opened the door, it was violently pushed open, almost injuring the woman who stood in front of it.

They yelled threats and pushed us aside with violence. No reason was given for the raid, no search warrant was presented.

We immediately returned to our rooms as they roved through the house. We heard doors and drawers rip open and dishes crash onto the floor as the group spread out through the house.

David was in our room, standing pale, half hidden behind the partially open door of a large armoire. Mother pulled down the bedding and silently motioned for him to lie down on the bed.

She piled the bedding on top of him and smoothed out the bedspread. Calmly and in total silence.

Then she motioned to me to get busy with something. This was a desperate gamble on her part.

If David was found, he would be taken away and probably shot as a deserter. Mother and I were also at risk since we would be considered accomplices; we would be jailed and/or deported.

The minutes crept by slowly.

Then our door flew open and one of the young thugs marched in, followed by a policeman, an elderly man, who looked very uncomfortable.

They began searching the room, opening drawers and throwing things on the floor. The policeman searched methodically, going around the room, until he reached the bed.

He took his baton and pushed it between the layers of bedding, then he called out to the fascist boy.

“Nothing here, brother! Let’s go on to the next room.”

He looked straight into Mother’s eyes and walked out.

I had been standing by the wall the whole time, holding an exercise book and pencil in my hand, pretending to study.

They pushed me aside a couple of times, but otherwise didn’t bother with me. It was difficult to control my hands so that they wouldn’t tremble.

I didn’t dare look in the direction of the bed or at Mother, even after they had left the room.

We both remained frozen, motionless. I feared that David would be smothered under the heavy eiderdown bedding. We prayed that the raiders would leave the house quickly.

They did finally leave, taking with them items they had grabbed from our rooms. Robbery had been the real reason for this raid.

We pulled the heavy eiderdowns off David. He was pale but none the worse for wear.

David managed to maintain a tiny opening at the back of the bed, by the wall. Hearing everything and had felt the push of the policeman’s baton.

He hadn’t prayed, or thought about what could happen to him. Just lain there, motionless.

Trying to act calm, we didn’t hug each other in triumph or celebrate David’s miraculous survival.

We knew that only one battle had been won and that the war was still on. There would be more raids of this kind, more risks and dangers.

I was then and I am still convinced that that policeman knowingly saved David’s life.

If the young fascist had discovered David after the policeman finished his search, he would have been accused of helping Jews. He would have been severely punished.

Yet this elderly man had put himself at risk. Here was one good gentile I will remember forever.

Not the only one I encountered during those dangerous months. Along with the butcher and the baker who set aside food for us.

The acquaintances who met us in the street or on a streetcar at some illegal time when we were not wearing the star and didn’t point us out to the fascists who were searching for people just like us.

I remember all these people. Their humane behaviour underlined the inhumanity and cowardice of the others.

And then there was my school friend, Joseph Kovacs.

False I.D.

I decided it was time to adopt the identity of a Christian boy. This would allow me to move around the city safely until the Russians liberated us.

I had maintained a good relationship with a gentile classmate named Joseph Kovacs. He had been a sympathetic friend who had proven on several occasions to have a friendly attitude, free of prejudice.

Early on, he had said that if things got very bad for Jews, he would do anything to help me out.

So one day in June, 1944, I walked over to his house and knocked on the door. Once he got over the initial shock of seeing me, I asked him if I could use his baptism and birth certificates.

Without hesitation, Joseph agreed to help me out.

A few days later, he brought me an envelope containing the documents. We agreed that it would be best not to meet again until the war was over.

At that point, we would celebrate our survival. We exchanged best wishes and parted ways.

I never did see Joseph again. I looked him up after the war, but didn’t find him or ever find out what happened to him and his family.

The Budapest Ghetto for Jews in Hungary WW2

We had friends and relatives in the Budapest ghetto, whom we hadn’t heard from since spring. I put together a small parcel of food, took out my Christian certificates and headed for the ghetto to visit them.

The designated area was about 6 or 7 city blocks, surrounded by a high fence, with only a handful of openings to the outside world.

These were guarded by young hoodlums to prevent the smuggling of food into the ghetto and of Jews out.

I walked up to the gate, waved my paper nonchalantly, and was let through by a policeman.

A young boy yelled at me:

“Bringing food for the kikes? You dirty Jew-lover!”

I just shrugged my shoulders and walked on.

I knew this part of the city well. The ghetto was the old Jewish quarter, and included the Great Synagogue of the city.

Now, after only a few short months, the ghetto had deteriorated so drastically that I felt like I was seeing the area for the first time. The full horror of the living conditions hit me hard.

What I saw was beyond my worst expectations. I had heard about the Polish ghettos, but this was Budapest, not some primitive city!

Food supplies had run out, garbage was no longer collected and diseases such as typhoid were rampant. Thousands of people were homeless.

Some had been forced to leave the crowded rooms assigned to them and some had never been assigned accommodation in the first place.

Dirty water ran along the gutters, carrying with it garbage, dead rats, faeces and urine. The schools were closed so children roamed the streets.

All the misery, poverty and suffering were out in the open, without shame or mercy.

The sidewalks were lined with people selling all kinds of useless merchandise, remnants from a distant “normal” life: books, pillows, clothing, even typewriters and record players.

Among the crowds filling the street, there were people on old bicycles or with pushcarts, carrying old people who were unable to walk or sick people who were too weak to visit the nearest “doctor’s office.”

In every corner and doorway, there were people lying prostrated or curled up in the fetal position.

Some were homeless; others were dead, simply left to be picked up later by the collection brigades and buried in large pits in one of the parks.

Bodies were buried quickly, without any attempt at identification. Minimum ritual was observed.

Someone said the El Male Rachamim at the graveside and there were no burials on shabbat and holidays.

Later, with the arrival of fall, when the air was cooler and the shortage of manpower was more serious, bodies were left at one of the dumping places.

Either one of the public parks inside the ghetto or the garden of the Great Synagogue. As winter came early this miserable year of 1944, the bodies soon froze together, forming solid, inseparable blocks of ice.

The cold at least eliminated the very real danger of a cholera or typhoid outbreak and reduced the urgency for quick burial.

Someone took pity on me, and guided me through the throngs towards a building that I barely recognized.

The building where my relatives lived. The courtyard was dark, but filled with children playing, jumping, and running around.

They all looked at me with suspicion. Someone whisked me up the stairs and called out for our relatives.

The whole visit took place in a furtive atmosphere. I quickly entered their apartment, every inch of which was being used.

It was difficult to move around; people were sitting or standing everywhere. After exchanging news about family members. Who was dead and who was still alive.

I handed over my small parcel and quickly left.

The air was putrid with the smell of rotting garbage, perspiration and other odours which hung oppressively in the air.

I became panic-stricken, pushing my way through the crowds like a drowning man trying to come up for air.

Afraid that the gates of the ghetto would close, that I would be trapped inside.

To become one of the living dead, wandering aimlessly on the street. Suddenly, I stood in front of the gates to the outside.

I walked outside, waving “good day” to the policeman standing there.

He muttered a lazy goodbye, not bothering to look at my identification papers.

I entered the ghetto several more times, under even worse conditions. The piles of dead bodies grew higher.

The barely alive bodies of women, children and old men, too weak from hunger to move, covered much of the sidewalks.

But my first visit had been the most memorable, frightening and depressing.

These were educated, middle-class Jews. after only three or four months of ghetto confinement they were living in conditions which, we had always thought, existed only in the most primitive villages and shtetls.

Stripped of all civility, all that remained was the struggle for the most basic daily existence.

My resolve to stay free became firm: I would never be forced to enter the ghetto or be locked up in one of the cattle cars and taken to the camps.

Luftwaffe: The German air force.

Eichmann, Adolf (1906-1962): Adolf Eichmann is the SS officer who was responsible for the murder of millions of Jews. Born March 19th, 1906, in Austria, he joined the Austrian Nazi party in 1932.

As an SS lieutenant colonel, he headed the Jewish office of the Gestapo and was largely responsible for carrying out the “final solution.”

He once said: “I will leap laughing to my grave because the feeling that I have five million people on my conscience is for me a source of extraordinary satisfaction.”

After being arrested at the end of the war, Eichmann escaped from an internment camp in 1946 and disappeared. The Israeli secret service found him in Argentina in 1960 and took him to Israel. His trial attracted attention around the world.

Charged with committing crimes against the Jewish people, crimes against humanity and war crimes, this nazi war criminal was found guilty and hanged on May 31, 1962.

Arrow Cross party: A Hungarian fascist party and movement, formed in 1937. Ferenc Szálasi was the party’s founder and leader.

Until the outbreak of war, the Arrow Cross party was largely considered an extremist fringe party, a collection of misfits.

In the 1939 national election, the Arrow Cross won 25% of the vote and became the most significant opposition party.

After Horthy’s attempt to sign a separate peace failed on October 15th, 1944, the Arrow Cross came to power.

Their brutal, murderous reign ended in January 1945 when the Soviets liberated Budapest.

concentration camps: After World War II started in 1939, some concentration camps were transformed into sites for carrying out genocide.

These camps, all in occupied Poland, are sometimes called “death factories.”

Many Jews were killed in the gas chambers of the extermination camps, as well as tens of thousands of Gypsies, homosexuals, political prisoners, Jehovah’s Witnesses and Soviet prisoners of war.

Prisoners managed to organize uprisings in a number of camps.

Auschwitz: The largest and harshest Nazi death camp, located in the southwest of Poland. Originally used as a concentration camp in 1940 (after the defeat of Poland), it became a death camp in 1942.

The camp included: Auschwitz I (Stammlager); Auschwitz II (Birkenau), the most populated extermination camp; and Auschwitz III, the I.G. Farben labour camp (also known as Monowitz or Buna).

As victims arrived by train from all over Europe, they were separated into two lines.

Men to be used as forced labour; women and children, who were to be killed in the gas chambers that day, or in a mass grave.

As many as 6 000 ruthless SS officers worked at Auschwitz.

It is estimated that one and a half million men, women and children were murdered there, making it the largest graveyard in human history.

Auschwitz was liberated by Soviet soldiers on January, 27th, 1945.

ghetto: During World War II, a section of a city in which Jews in Hungary WW2 were required to live.

Residents of the ghetto were barred from engaging in any activity outside of the ghetto, including visiting and shopping.